Blogger: Shannon Cain

Executive Director, Kore Press

Book Review

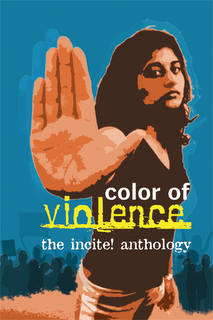

Color of Violence: the INCITE Anthology

South End Press, 2006

This article will appear in the next issue of the Sonora Review.

How does a white woman respond to a book about violence written and edited by women of color? The day I contacted South End Press to let them know I’d like to review their 2006 book Color of Violence: The INCITE! Anthology, I wasn’t thinking about what it would mean for me, a reader whose race privilege puts her outside its contributors’ experiences, to offer my perspective, much less to challenge or to agree with its contents.

Who am I, was my realization somewhere around page two, to enter into this dialogue? On more than one occasion when I engaged the topic of race—when I elected to acknowledge that racial dynamics were at play in a given personal or professional situation—I ended up in a morass of anxiety and misunderstanding. Why am I surprised when the dish I cook ends up disastrous, given the primary ingredients I bring to the recipe are blundering good intentions, nervousness around the topic, and privileged ignorance?

So I feel a morose kinship with those early pioneers of the domestic violence movement, the white women whose groundbreaking work in the late seventies and early eighties sparked a massive social consciousness-raising around the issue of relationship violence and created fundamental shifts in the way law enforcement, health care and social services recognize and deal with battering. Kinship because a generation ago it was perhaps their own privileged ignorance that allowed the social justice ethic of that movement—which we are reminded in the introduction of Color of Violence had been largely authored by women of color, particularly Black lesbians—to all but disappear from the antiviolence organizations of today. We are now stuck with a “movement” that long ago lost its radical social change edge. It has transmogrified into a network of government-funded social service charities, emergency room procedures that medicalize the issue into one-size-fits all policies, and laws that often land the victim/survivor of abuse in the criminal justice system alongside her abuser.

The thematic thread that runs through Color of Violence is not so much that women of color are subject to violence in particularly cruel and complicated ways, or that we as a society have failed to see that the intersection of gender, race and violence is rigged with explosive devices. Certainly these are the elements upon which the book is based; the reason for its birth. The thread that shows up in every essay, the one its contributors tug at relentlessly, is this: the state—in the form of law enforcement, medicine, criminal justice, “national security,” and even nonprofit social services—is complicit in the continuation of violence against women of color.

It’s a daring premise, and one that the Color of Violence contributors defend in terms both academic and personal. Through intellectual discourse and gut-level anecdote, we are introduced to an imposing number of complexities. Complexity #1, for example: the nonprofit industrial complex and its rape crisis centers and shelters that seek to eradicate violence by working in cooperation with a criminal justice system that has been brutally oppressive toward people of color. Complexity #2: the expectation by communities of color that women “keep silent about sexual and domestic violence as a way to maintain a united front against racism.” Complexity #3: If you’re a Black woman in Chicago versus a Palestinian immigrant in Canada versus a maquila worker in Ciudad Juarez, violence can play out with both staggering differences and universal similarities.

While I admire the diversity of experience and viewpoints in Color of Violence, the volume’s refusal to set a rhetorical tone was difficult to take. A transcript of a woman’s wrenching oral storytelling is set side-by-side with what appears to be an excerpt from another contributor’s PhD thesis. The end result is that editorial cohesion is sacrificed; the volume has the feel of having been assembled by committee.

In an anthology of such diversity and sheer number of essays (thirty), there are bound to be a clunker or two. I was disappointed by Sylvanna Falcón’s “‘National Security’ and the Violation of Women: Militarized Border Rape at the US-Mexico Border.” While Falcón makes an incontrovertible case for the culture of racism and misogyny and the lack of accountability that allows Border Patrol and other law enforcement agents to rape women attempting to cross the border, she fails to convince me of her premise that “rape is routinely and systematically used by the state in militarization efforts.” I began her essay eager to believe, eager to see the evidence of actual state sponsorship of rape, but ultimately was left wondering how unsubstantiated claims such as Falcón’s serve the movement. I'm uncomfortably aware that the insistence on providing “proof” of what disenfranchised people know is true has been historically used as a way of invalidating their experiences, so it feels like treachery on some level to suggest the need for evidence of Falcón’s claims. Still, it would have been enough—heartbreaking and rage-inducing enough—simply to document the culture of bigotry, the premeditated nature of assaults by serial rapists wearing the Border Patrol uniform, and the malevolent results of official passive neglect.

By and large, the essays in this volume show that anecdotal evidence is plenty good enough. Most effective are those pieces that ignore expectations that women of color “prove” (to the patriarchy, no less) what they already know to be true. Dana Erekat’s “Four Generations of Resistance” is a gorgeously crafted piece of creative nonfiction framed in the second person: a “testimonial” told as “true stories intertwined into one” in which the reader is invited into the experience of an intergenerational quartet of Palestinian women, framed as a tag-team account of everyday horrors that bring into sharp focus the unrelenting struggle against violence that is their lives.

The question is whether we can hear these stories. How can a country that seems to have overlooked the obvious reality that recent schoolhouse sex abuse and murders in Amish county and in Colorado were hate crimes against girls manage to understand the layers of meaning behind the rape and beating of a Mexican migrant by a Border Patrol agent? I am beholden to the contributors of this volume for their attempts to shift a poisonous culture that debases us all. It is possible—and indeed this anthology makes one believe it is probable—that women of color will lead us through and beyond our collective ignorance.